A Beginner’s Guide to Art Movements (and Why Art History Actually Matters) - Pt. 3

I’ve written two posts under the question “Why is art history relevant?” without really answering the question (read Part 1 & Part 2 here). Today, I’m finally adding some more substance to the conversation.

Art can be confusing. You might hear people throw around “modern” and “contemporary” like they mean the same thing (spoiler alert: they don’t). But knowing the basics of art history isn’t about sounding clever or impressing people who know less than you. It’s about unlocking the stories, the why behind the masterpieces, and making art actually make sense.

The best place to start, in my opinion, is with the different art movements. Art theory is another great place, but in my humble opinion, that holds more value for artists or those working in the art world.

Art has always been a record of the human experience with the world around us, so history and art go hand in hand. Understanding world events before, during, or after the creation of an artwork is a great first step. That should be followed by looking into what was going on in the artist’s world. These might be personal or family events, regional developments, or broader cultural shifts. Religious movements, for example, are especially revealing when looking at the Baroque period and the Protestant Reformation happening at the same time.

Here’s a quick rundown of major art movements and what to look out for, so your next museum visit feels more like a conversation with history.

(This is by no means a comprehensive list and is based on Western art, which is what I’m most familiar with.)

Classical (Ancient Greek & Roman, ~800 BCE – 500 CE)

Art was created to reflect ideal human forms and uphold balance, beauty and order in both life and architecture. Look for calm expressions and ideal proportions. These weren’t portraits, they were ideals. In architecture, think columns, domes and marble built to impress gods and mortals alike.

Notable names: Phidias, Polykleitos

Hadrian’s Gate (Athens, Greece, 2010).

Medieval (Byzantine, Gothic, ~500 – 1400)

Art aimed to teach religious doctrine and glorify God in a time when most people were illiterate. Flat figures, gold leaf, and heavy religious symbolism. Expect saints with halos and plenty of symbolic animals. Architecture went full fantasy: stained glass, spires, and cathedrals that reached toward heaven.

Notable names: Giotto di Bondone, Giovanni Cimabue

Supplicant Soul between Saint Peter and Saint Paul, by the Master of Soriguerola, likely around 1320. (Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2019)

Renaissance (~1400 – 1600)

Artists focused on anatomy, perspective, and realism, as if the veil between heaven and earth had been pulled back. They sought to reconnect with humanism and classical knowledge, celebrating the individual and divine. You'll see Biblical scenes with lifelike bodies and serene expressions. Domes and mathematical precision dominated architecture.

Notable names: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini

Blessed Soul by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1619) (Vatican Museums, 2024). (Photo credit: Shaun Putter)

Baroque (~1600 – 1750)

Art was a tool for persuasion, designed to awe and emotionally engage viewers during religious and political upheaval. Think grandeur, drama, and movement. Dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro), theatrical compositions, and saints mid-miracle. Baroque churches practically scream “look up” with ceiling frescoes that defy gravity.

Baroque art emerged in response to the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. The goal was to strengthen religious faith through emotionally engaging, visually dramatic art. The Catholic Church, in particular, embraced this style to reinforce its doctrines and inspire piety.

Notable names: Caravaggio, Rembrandt van Rijn

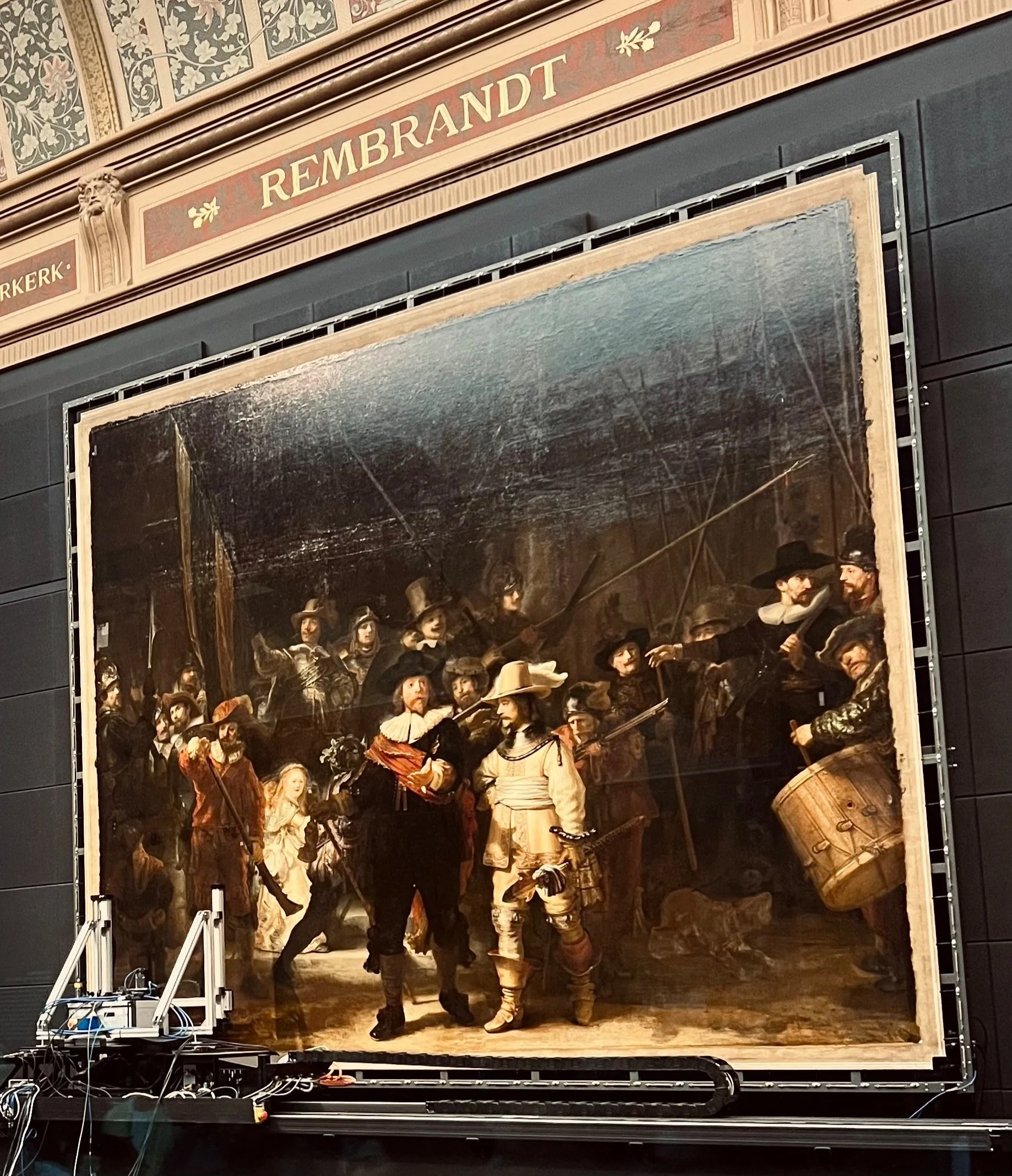

The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn (1642) (during Operation Night Watch at the Rijksmuseum in 2023, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Rococo (~1720 – 1780)

Art became a form of escapism for the aristocracy, celebrating pleasure, luxury and leisure. Soft pastels, playful mythologies, and flirtatious aristocrats pretending to be shepherds in dreamy gardens. Interiors were packed with ornament, including curls, curves, and chandeliers.

Notable names: Jean-Honoré Fragonard, François Boucher

The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1767-1768). Image from World Art: The Essential Illustrated History. Flame Tree Publishing, 2006.

Neoclassical (~1750 – 1830)

Artists returned to moral clarity and classical ideals as a reaction against the excess of the Rococo and in support of Enlightenment thinking. Stoic heroes, clean lines, and moral seriousness. Expect toga-clad figures doing noble deeds. Architecture mirrored ancient temples with symmetry and clarity to signal virtue and reason.

Notable names: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jacques-Louis David

The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David (1793). Image from World Art: The Essential Illustrated History. Flame Tree Publishing, 2006.

Romanticism (~1800 – 1850)

Art was created to explore intense emotion, nature’s power and the sublime, often in defiance of rationalism. Wild landscapes, emotional intensity, and a love of the sublime. Think shipwrecks, lightning storms, or lone figures lost in thought. Gothic ruins and moody lighting show up a lot.

Notable names: Eugène Delacroix, Francisco Goya

Detail from Le Puits de la Casbah Tanger by Eugéne Delacroix. Image from World Art: The Essential Illustrated History. Flame Tree Publishing, 2006.

Realism (~1840 – 1880)

Artists aimed to depict the world truthfully, shedding romantic idealism in favour of everyday life and social realities. No fluff, just life. Artists depicted workers, daily life, and ordinary scenes without embellishment. Clothes are worn, buildings are plain, and it often feels like a candid snapshot of real history.

Notable names: Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet

Transport of Colonial Soldiers by Isaac Israels (1883-1884) (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 2023).

Modern Art (~1860s – 1970s)

Modern art is not a single movement, it is a rebellion. This era includes Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art. Artists started asking, what if we don’t do it the old way? Do not expect realism, expect ideas.

Impressionism (~1860 – 1890)

Art captured fleeting moments and changing light, challenging traditional techniques in favour of perception and spontaneity. Loose brushstrokes, natural light, and moments mid-motion. Think gardens in bloom and dancers mid-twirl. It’s less about precision and more about capturing an atmosphere.

Notable names: Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (my favourites!)

In the Café by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1877) (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 2024).

Post-Impressionism (~1880 – 1905)

Artists pushed beyond Impressionism to explore structure, emotion, and personal symbolism in their work. Bolder colours, stronger outlines, and deeper emotion. Landscapes may feel dreamlike, and portraits often carry psychological weight. Still-lifes are more symbolic than literal.

Notable names: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne

Sunflowers by Vincent Van Gogh (1888-1889) (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 2023).

Cubism (~1907 – 1920s)

Artists deconstructed form to explore multiple perspectives and question how we see and represent reality. Forms reassembled to show all sides at once. Faces, instruments, and interiors may appear fragmented but are carefully composed.

Notable names: Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque

Woman in Hat and Fur Collar (also known as “Marie-Thérèse Walter) by Pablo Picasso (1937) (Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2019).

Dadaism (~1916 – 1924)

Chaos, on purpose. Dada artists rejected logic, beauty, and “serious art.” Expect absurd collages, found objects (like a urinal titled Fountain), and a feeling of “is this even art?” That is the point.

Born out of the trauma of World War I, it challenged tradition and inspired future performance art.

Notable names: Marcel Duchamp, Jean Arp

The Great Dancer by Jean Arp (1926). Image from World Art: The Essential Illustrated History. Flame Tree Publishing, 2006.

Surrealism (~1920s – 1950s)

Dream logic, uncanny symbols, and impossible spaces. Art aimed to tap into the subconscious and explore dreamlike, irrational imagery as a route to deeper truth. Think melting clocks and dreamlike landscapes. Architecture sometimes twists or floats entirely.

Notable names: Salvador Dalí, René Magritte

Print copy of Man in a Bowler Hat (“L’Homme au chapeau melon”) by René Magritte in an AirBnB in Rome, Italy. (Original painting dated 1964)

Abstract Expressionism (~1940s – 1960s)

Art became a direct expression of the artist’s emotions and inner psyche. Gesture became the subject. No figures or scenes, just brushwork, colour and scale that evoke emotion. It’s not “what is this” but “how does this make me feel?”

Notable names: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko

Number 6 by Jackson Pollock (1948). Image from World Art: The Essential Illustrated History. Flame Tree Publishing, 2006.

Pop Art (~1950s – 1970s)

Bold colour, familiar imagery and clean lines. Art commented on mass media, consumerism and celebrity culture using the language of advertising and pop culture. Soup cans, comic books and celebrities. Familiarity is key (or consumerism if you want to go deeper).

Notable names: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein

Part of Queens by Andy Warhol (1885) (Paleis Het Loo, Netherlands, 2024).

Contemporary Art (~1970s – now-ish)

This is where art went rogue. Art reflects the diverse concerns of modern life, from politics to identity, and often asks questions rather than providing answers. Everything is fair game, including video, performance, digital work, and even scent. Ask what the piece is doing, not just what it is.

Museums may feel more like think pieces than galleries. That is intentional.

Notable names: Yayoi Kusama, Jane Alexander

African Adventure by Jane Alexander (1999-2002) (Tate Modern, London, 2017).

Most museums are arranged chronologically, which makes visits simpler if you have the background above.

But remember, understanding art history means trying to understand the history of the world, so start small.

Choose one or two movements that speak to you for any reason. Read about world events from that time. Google who commissioned the art and who the major artists were. Narrow it down to the country the museum is located in, since many museums already focus on a specific niche.

Then, walk in with a bit of background and no rigid expectations. That way, you won’t be disappointed by the size of the Mona Lisa, but instead captivated by Leonardo’s use of sfumato. (This is a painting technique that softens transitions between colours to mimic the way our eyes perceive out-of-focus areas. It is a hallmark of the Renaissance.)

You do not need to read thick books on art history to enjoy a museum (though I highly recommend it). You just need to spend a few minutes online and make a short list of things to look for.

I promise, your experience with art will change.

And who knows, maybe you will be able to mimic Richard Gilmore’s “frown, step back, wrinkle, and sigh” with more authenticity. (Gilmore Girls fans, you know.)

P.S. All photos are my own (taken of the artwork itself or images thereof in World Art: The Essential Illustrated History, Flame Tree Publishing, 2006), or my talented husband's where noted.